Except you were a member of repressive cult that banned radios, going to the club and access to the internet, there was no way you didn’t hear “Turn Me On” in 2004.

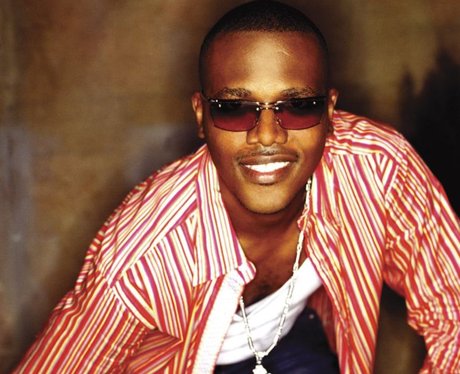

The seductive party jam became the biggest soca hit to emerge from the Caribbean in 20 years and for many young Nigerians, it was our first introduction to the genre. Some of us were so green to soca music that we initially thought that everything with a Carribean influence was a Sean Paul song – Google wasn’t a very competent friend back then – but “Turn Me One” actually belonged to a little-known artist from a tinier Caribbean island called Kevin, no pun intended.

Kevin Lyttle initially recorded “Turn Me On” in 2001 on his native island of St. Vincent as a soca ballad, but the song became a minor hit throughout the Caribbean. With the success of Sean Paul at the time, big labels had their eyes on Caribbean music, Lyttle signed with Atlantic Records in 2003 and a remix version of “Turn Me On” (featuring Spragga Benz) was officially released as a single. The label then promoted “Turn Me On” until Kevin’s shrill-like voice was heard on dance floors worldwide.

“Turn Me On” eventually became a worldwide hit in 2004, reaching number 4 in the US, number 3 in Australia and in the top 5 in many European countries. The smash single would go on to sell 6 million copies worldwide on Atlantic Records, in addition to Kevin’s self-titled debut album selling 2 million copies. However, in a recent interview on Ebro In The Morning on Hot 97 New York, Kevin Lyttle disclosed that he hasn’t seen a single dollar in royalties, 13 years later.

I haven’t see the books yet, I’m still recouping, according to them. I’ve never seen a cent from them [Atlantic]. They’ve sent statements [but] they’ve never sent me anything that says – okay, you’ve made some money… These things happen all the time.

‘Recouping’ means that the label hasn’t paid Kevin yet because they haven’t recovered all the money they spent in marketing and distributing his project. Interestingly, a rough calculation of the gross revenue that the label made on Kevin’s single and album alone amounted to around $47m, and this doesn’t even take into account the soca singer’s other reasonably successful singles. During the interview, Kevin also disclosed that he was given a $2m advance, creating a wide margin between what he was fronted and what the label purportedly made. This wide margin puts a huge question mark on Atlantic’s reported claims that they are yet to recoup on their initial investment.

However, even though the label seems to have one-upped him, Kevin Lyttle, isn’t hurting financially. He says he has made a lot of money from the song’s publishing and from performing in several countries around the world for the past decade-plus, including Nigeria in 2015. In addition, the singer was actually in New York to promote his latest single “Slow Money”, so he has been able to move on since leaving Atlantic Records. But the money Kevin has made from other streams doesn’t mean he isn’t going after his “Turn Me On” royalties any longer. According to the singer:

We have been [trying to fight this] but as usual, we get the – ‘Oh, he hasn’t recouped yet, we can’t find the books, the books are in a warehouse somewhere, and that’s so long ago… and statutes of limitations’…

Kevin is honest enough with himself to take responsibility for entering into a record deal where he got the short end of the stick and explains that being that he was an outsider to the music business in America, naivety played a big part.

I come from a little island in the Caribbean, and then I get pushed to this lawyer, and you find out the lawyer is helping your management too… And it’s all kinds of conflict of interest… A lot of young artists go through this in the beginning, especially if you have a bit of education, you think you can handle it. But then when it comes down to it, the beast that you have to deal with – you get shafted somewhere along the way.

Kevin’s story presents a teachable moment for African artists who have been signing all sorts of record deals with the majors. Labels are doing the same thing with African music in 2016/17 as they did with Caribbean music in the early-2000’s, and the same way they left artists like Kevin Lyttle high and dry when they lost interest in island music, is the same way so many African artists will be left worse off when this wave ends.

The key is therefore for African artists to sign water-tight contracts and surround themselves with experienced handlers from countries that they are now doing business in, that understand the landscape. These handlers should preferably be independent from their label, booking and management reps, to avoid conflict of interest issues. This isn’t Naija anymore, not everything ‘goes’. We’ve already seen Phyno’s naivety be exposed on the world stage, and he will not be the last artist to be left stranded like a deer in headlights.

Another key is to remember that this ‘Afrobeats’ phase will end, or at best it will slow down, so our artists have to play the long game and not be short-sighted. Bright lights and worldwide recognition is nice but they have to have a plan for when the attention and excitement dies down. That’s the only way, like Kevin, they can stay rich and the world will still care about their music in 13-14 years to come.