Nigeria recently marked World Music Day with the rest of the world but for me, the day was 2-parts celebration, 1-part reflection. While Nigerian pop music has never been as accepted globally as it is right now, it is frustrating that we’ve allowed the imperfect title of ‘Afrobeats’ to define its rise.

There is no doubt that Nigerian pop music is on the up and up, the biggest song in the world last year, Drake’s “One Dance”, had Yoruba in its lyrics and a Nigerian superstar in Wizkid as a collaborator, while several songs released since then have copycatted its sonic template. Wizkid’s own single “Come Closer” has charted in at least 6 different countries worldwide and helped to build a buzz for his major label debut Sounds From The Other Side due out this week.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xUetSQlxOWY

The singer has been the most successful Nigerian export, so far, but Davido, Timaya, Tiwa Savage, Yemi Alade and Burna Boy are also pulling their weight abroad, while new entrants Maleek Berry and Patoranking are doing their bit to put the country’s music on the map. Even the little-known Ayo Jay scored a gold-selling single with “Your Number”, and is just one out of over half a dozen Nigerians signed to major label deals, publishing companies or management contracts.

These artists are helping to change the global soundscape but when they are individually asked to describe the kind of music that they do, you get uninspired responses – anything from Wizkid’s carefree ‘I make good music’ to Davido’s painfully generic ‘Afrofusion’. There isn’t one word that the artist community in Nigeria uniformly uses to describe our contemporary pop sound, so what has inadvertently happened is that the unimaginative title of ‘Afrobeats’ has come to stay – nature and vacuum.

DJ Abrantee, a UK-based DJ of Ghanaian descent, is widely believed to have popularized the term. Through his popular weekly radio show, Abrantee used ‘Afrobeats’ to describe the music and culture being shared between young Nigerians and Ghanaians, especially in the melting pot that the U.K. had become for immigrants from both countries. In a 2012 interview, the DJ explained, “for years we’ve had amazing hiplife, highlife, Nigerbeats, juju music, and I thought, you know what, let’s put it all back together as one thing again, and call it Afrobeats, as an umbrella term.”

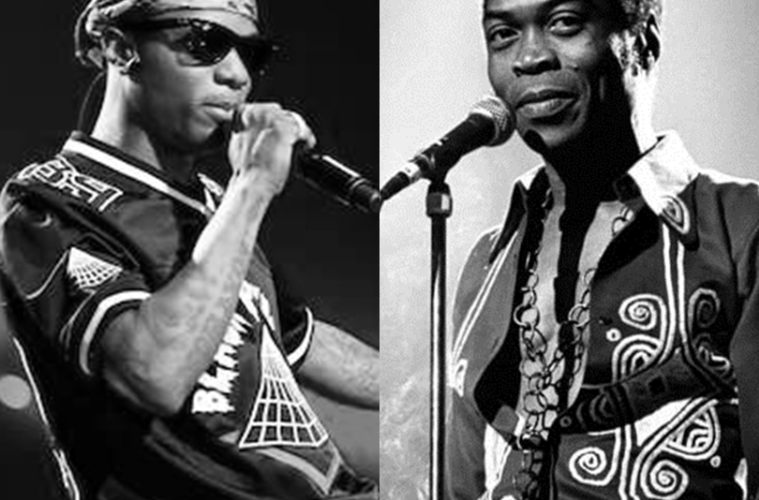

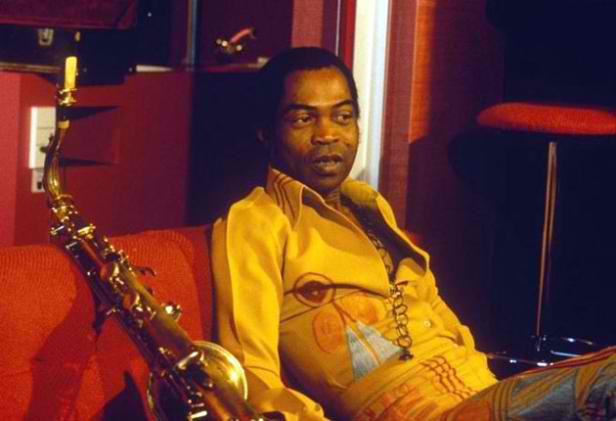

But the term ‘Afrobeats’ is a problematic for a number of reasons – the first is that it tiptoes too close around Fela’s hallowed music legacy. Even though today’s pop music is culturally and stylistically different from the original Afrobeat sound Fela birthed in the 70’s, we’ve somehow ended up in a funny position where pluralizing a word gives it a whole other meaning from its singular form. This reminds me of the time a former Senate President insulted our collective intelligence by claiming that there was a difference between Evan and Evans Enwerem.

The second problem is the same problem with all genres prefixed with “Afro” – Afropop, Afrosoul, Afrotrap – it isn’t uniquely Nigerian. Obviously, contemporary music from Nigeria and Ghana share a bond that stretches from E.T. Mensah and highlife in the 50’s to a music mutant like Mr. Eazi in 2016/17, so the 2 countries are musical Siamese twins at this point, but “Afro” denotes something bigger than just the 2 of us and bunches us with the rest of the continent. We cannot complain about Africa being called ‘a country’ and then turn around to embrace the retrogressive mass labelling of all of our pop music, that’s being intellectually dishonest.

The third problem is the fear of every Nigerian artist being pigeonholed into one sound, the same way every artist coming out of Jamaica is assumed to be in the dancehall/reggae category. The legendary DJ Jimmy Jatt articulated that fear best in a recent interview when he said “I think it’s limiting when we try to generalize our music under Afrobeats, because under this ‘Afrobeat’, you have people doing dance music, rappers are there, R&B artists are there and they are all categorized under Afrobeats artists.”

While I see sense in what Jimmy Jatt is saying, I think it’s important to retain the identity of our generic pop sound, while we allow specialists like rappers and R&B singers be, as Jimmy suggested, rappers and R&B singers.

Through the years, we’ve successfully imported global genres like hip-hop, soul and R&B, and maintained indigenous genres like highlife, the original Afrobeat and fuji, but artists whose music colors outside the lines of traditional genres also need an identity and I don’t think Afrobeats is good enough.

That’s why I had called for a ban of the term ‘Afrobeats’ but only on World Music Day every year because, especially with the foreign media picking up the term, I realize it’s probably too late to do anything else about it. Besides, even if it wasn’t, you don’t get the sense that there is an appetite within the artist community or the local media or at award show academies to switch things up. Nigerian pop music will continue to grow in the next 12 months and by the next World Music Day, it will be even bigger than what it is right now, but you can’t help but feel that we’ve missed a golden chance to control our own narrative.

Originally written for the Guardian Nigeria for World Music Day