1. Legacies Never Wrinkle, Or Fold

Despite the growing popularity of the term, and increasing successes of a couple of purveyors, Afrobeats has a gnawing lack of peculiar sonic identity. Caring less about stylistics and more about geography, it’s saddening that Afrobeats simply lumps every contemporary genre of music being made in Africa into a giant blob. While it has continued to ignorantly foster the notion that Africa is one big, giant country – despite the name being inspired mainly by music from Nigeria and Ghana, maybe we can agree that the term, however wrong, has helped improve awareness of the great music being made here to more people across the Atlantic.

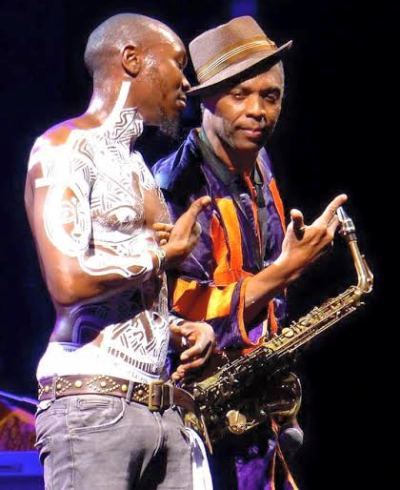

Seun and Femi Kuti performing on stage

Another objection raised about Afrobeats is in how it seemingly infringes on Afrobeat, the genre of music patented by Fela in the early 70s. It’s no news that names are of utmost significance in Africa, since they are considered to speak a thousand volumes, and with both words being differentiated by an ‘s,’ it somewhat justifies the discomfort it causes those who aren’t in favor of the close contact between both terms. Although the nominal margin between Afrobeats and Afrobeat has the thickness of a broomstick, any sort of inspection does reveal more substantial differences.

Where Afrobeats is an unclear and disproportionate amalgamation of various genres of contemporary African pop music, the form of Afrobeat is undeniably distinct both in sound and content. A blend of the improvisational elements of jazz, greasy funk/soul music and traditional Yoruba folk insertions, Afrobeat is a composite, ever steamy pot of musical gumbo engraved in the complex identity and musical virtuosity of its progenitor.

Besides the fact that the primordial stage and the prime of Afrobeat is attributed to Fela, his stance as a sociopolitical dissident via his music makes his mythos all the more towering. This defined pathos of Afrobeat as music for social, political and conscious emancipation for Africans is a tangible differential factor from Afrobeats.

The current class of Afrobeats artists might be taking the world by storm at the moment, but none can lay claim to having created a genre or even much less, constantly making music that speaks to current social conditions. It’s why the popular image of Fela – bare-chested, saxophone torso around his neck and both hands raised up with balled fists – still in many ways depict the pinnacle of Nigerian music.

Probably an exaggeration, but it’s still acceptable to describe Fela as Bob Marley, James Brown and John Coltrane balled up into one person. He’s the inescapable shadow in Nigerian music whose impact will continue to reverberate through time. Legacies like that of Fela are not only built to withstand the test of time, but also almost impossible to surpass.

2. Two Scions, One Dynasty

It could be intimidating for children of impactful artists to live up to expectations, especially when they’re toeing the same artistic path. For Femi Kuti and Seun Kuti, the oldest and youngest sons of Afrobeat’s chief architect respectively, escaping their father’s shadow is an order taller than the tower of Babel. By virtue of their names and familial bond, there will always be an invocation of their father surrounding their endeavors. Instead of this causing any form of disdain, they’ve both leaned into the blueprint created by Fela, extending the durability of Afrobeat into these modern days and making it into a family heirloom.

Following a laid down ethos is in its own way a form of homage, but both artists have also been able to etch themselves into the DNA of Afrobeat through the balancing act of recycling and originality. In sound also, Afrobeat follows the same tightrope walk, balancing on being highly repetitive but never lacking dynamism. The foundational elements stay the same, but the infinite amount of polyrhythmic variations and combinations makes sure there’s never lack of experimentation.

Femi and Seun started their music careers playing with the Egypt 80 band, at different times though, acquiring the rudiments of Afrobeat composition straight from the source during these formative stages. Seun eventually took over leadership of the band after Fela’s death in 1997, and by that time, Femi had been recording and performing music with his own band Positive Movement, which he formed in the mid to late ’80s, after he had lead Egypt 80 during Fela’s prison stint in the early ’80s.

Both sons are former apprentices of one master, continually applying those lessons to their career, but with subtle shades of differences. In as much as the heels of their music is firmly dug into Afrobeat, they’ve both been able to add to the essence of the genre, individually. Especially vivid is Femi’s infusions of electronic music and hip-hop.

In their adventurousness, though, a common characteristic of Femi and Seun’s music is in how it offers a more streamlined version of Afrobeat. The grooves are ever hypnotic, but with songs clocking in at lesser minutes, their outputs are less head spinning, but equally – if not a little more – accessible, and still ever tilted towards sociopolitical topics.

Enunciating the troubles of the African experience is the embedded idiosyncrasy of Afrobeat, making it impossible to discuss the genre without referring to activism. With Nigeria somehow reveling in a seemingly permanent cycle of rot, Fela’s music from 30 to 40 years ago could still pass for anti-establishment music today. But in as much as the past serves as a potent reference point, the importance of highlighting the present on wax can never be understated.

3. One People, Black Nation

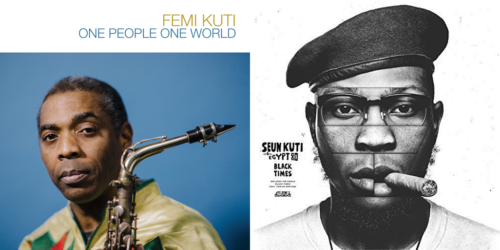

With the dilemma of redundancy, finding new ways to say the same ol’ things is almost impossible and even unnecessary, since the same stark conditions still need to be addressed. Both Femi and Seun have been consistent in doing that with their music and albums, and are still singing the Nigerian blues in present tense on their respective new albums – Femi’s One People, One Nation and Seun’s Black Times with Egypt 80, both recently released within a week of each other. Nuances differ slightly significantly on both albums, but there’s a shared kinship of making social music to spark a change.

Easy to spot, the different auras both album covers exude is the first notable disparity. The image of Femi – with visible grey hair – sitting with his saxophone by his side on the front jacket of One People depicts a staid, elderly cool. It’s contrary to the rebellious image projected by Seun on Black Times – an up close picture of his face with a soldier’s beret on, dark shades and a fat blunt in mouth. Both pictures are speak a thousand words, with the traits of each album being distilled into these images.

The title track of One People, One World finds Femi standing on the soap box, preaching the gospel of love, light and togetherness. Highlife guitar licks, bursts of joyous horn harmonies, and crashing cymbals of the propelling drums creates a multicolored atmosphere for a world party filled with laughter and positivity. “Racism has no place, give hatred no space,” Femi implores on the stellar cut, with several iterations of this message permeating through a major portion of his album.

Also hardwired into One People is copious amounts of hope. “Africa Will Be Great Again” opens up the album, a declaration of better days ahead, provided rampant corrupt practices by politicians is stopped. It’s hard to believe in Femi’s foresight, since to many, his advice would probably fall on deaf ears. The tone of disgust at such highhandedness surfaces when he reprimands the actions of politicians on a few scathing tracks. Plaintive and slow boiling, “Corruption Na Stealing” is as already explained in its title, and “Dem Militarize Democracy” is dismissive of Nigeria’s current civil government system, pointing at the heavy involvement of ex-military men, name dropping some “master coup plotters” for good measure.

Even while displaying angst, the elder statesman’s tone in Femi’s voice is always apparent, such that a nominally implicating song like “Dem Militarize Democracy” still carries a calculated, sage-like candor. Where Femi favors being more incise in addressing issues, Seun is quite blunter compared to his elder sibling. An example is the contrast of Seun’s own nominal attack at a recent ex president on “Theory Of Yam And Goat” – the last song on Black Times, which is more heady and nonchalantly exuberant.

In claiming to embody the spirits of black men widely regarded as champions of various social struggles like Nkrumah, Lumumba, Marcus Garvey, Fela and Beko Kuti on “Last Revolutionary,” there’s an easily perceived brashness Seun exudes that gives his words conviction. Not only is he invoking heroes past, but by also referring to himself as “General Kuti,” there’s a radical and rousing approach to his music, aimed at lighting the embers of revolution.

Apart from the Indian hemp extolling “Bad Man Lighter,” Seun’s go-to cadence on Black Times is mostly aggressive, infused with a measure of deadpan humor. The rattling “Kuku Kee Me” expands on a recognizable phrase to any Nigerian, lamenting the uphill struggle to survive as a common citizen in the country. In battling this social injustice, Seun demands that people be more assertive in their demand for change, hurling out declarative statements on steely cuts like “Corporate Public Control Department” (“all power to the people”) and “Struggle Sounds” (“na the iron nation go fight oppression”).

Seun’s millitant outlook invokes a likeness to Malcolm X, in comparison to Femi’s palette of highly needed philosophical platitudes which tilts toward being more Martin Luther King Jr. in nature. In spite of these differences, it’s obvious that both are expressing a genuine concern for the country’s current dilapidated state, with a call to make amends for better days.

“It takes the wisdom of the elders and young people’s energy,” posits American rapper Common, on the Oscar winning “Glory.” The above quoted line underscores why it is obstinate to argue which outlook on Femi and Seun’s albums is much needed or more potent at the moment. Especially with election season fast approaching, a mix of perspectives is required. Both have been offered on One People, One World AND Black Times, by two kings of one potent tool: Afrobeat.