A new Beyoncé album is a big deal. Scratch that, a new Beyoncé album is a HUGE deal. The iconic singer’s album sales may have plateaued in recent years but her cultural impact somehow continues to find new spaces to rise to.

Beyoncé released her latest studio album, The Lion King: The Gift, yesterday. The album was not only inspired by The Lion King, but also by the continent that inspired the original Disney movie and its 2019 live-action remake. Not to be confused with the movie’s original soundtrack, which was released last week, Beyoncé says her album is her personal “love letter” to Africa. Through the years, the pop star has shown a keen interest in connecting with her African ancestry through the arts, so an album dedicated to the continent doesn’t seem entirely opportunistic. But to view her latest musical excursion as some act of cultural altruism designed to please all Africans would be naive. Beyoncé has identified one of the final frontiers of global music and now has the opportunity to be an early curator of its current revolution.

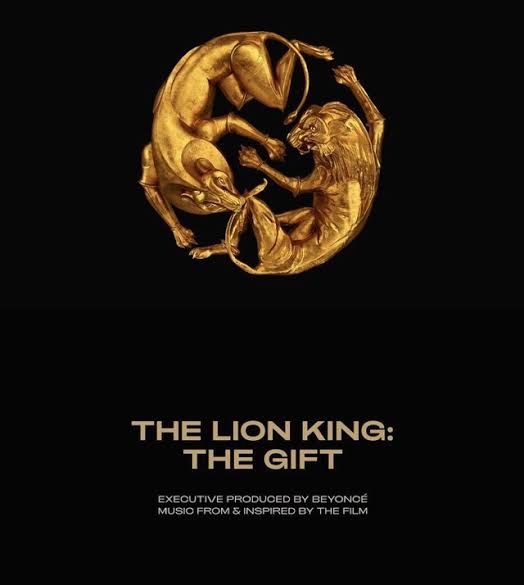

On this go-around, the queen of surprise albums has surprisingly chosen a conventional rollout. The Lion King album was set up properly: Beyoncé granted a rare interview to speak about working on it, the project had a pre-announced release date and the album cover and tracklist were shared with the public beforehand. All this generated a buzz, with music fans around the continent eager for their local musicians to receive a co-sign from one of the greatest artists of all time.

But that joy was tainted slightly when the album tracklist came under the type of microscope that would make a pan-African like Kwame Nkrumah turn in his grave. Beyoncé’s Lion King album featured 10 African artists: 7 of them were West Africans, 1 Central African, and 2 South Africans. An online fight for “federal character” but on a continental level ensued, with many Eastern Africans questioning the under-representation of their region on Beyoncé’s album. Even though their sense of entitlement was glaring, their argument didn’t seem altogether unreasonable. You cannot say an album inspired by a movie set in one part of Africa contains so many artists from another part, it’s geopolitically and culturally inconsistent.

Although it’s never explicitly stated, The Lion King was probably set in East Africa. The movie might have been fictional but the foundation it was built on was very real. For instance, the iconic opening song and the phrase “Hakuna Matata” are in Swahili, which is a language spoken by millions of East Africans. And since the producers researched the film in Hell’s Gate National Park in Kenya, we can probably conclude that Pride Rock and all of its animals are somewhere in Kenya too.

This is quite dissimilar from another pro-African Hollywood release, Black Panther, which picked its cultural influences from all over Africa. Nonetheless, the Kendrick Lamar-curated soundtrack for the film featured emerging gqom artists and was credited with putting a global spotlight on the South African music genre. Probably sensing a missed opportunity for East African artists, the outspoken Victoria Kimani was one of the leaders of the online mob that questioned the tribal under-representation on Beyoncé’s own album. She lamented: “As much as we celebrate with our fellow Africans, the obvious exclusion of Kenyans/East Africans on this soundtrack is depressing.” “The movie was based in Kenya”, she added.

Eastern African countries inadvertently led a lot of the cultural conversations in the 90’s when the first Lion King was made. At the time, it was mainly outsiders that told Africa’s stories. Much of the aesthetics of the continent were therefore shaped by the safaris and wildlife centers that were often Western tourists first and last point of contact with Africa. Thankfully, Africans are telling their own stories more and more through film and music. With music in particular, the West African-originated Afrobeats has emerged as the most popular genre on the continent by a wide margin. In fact, it’s arguable that, with their destination festivals and widely popular tropical sound, the genres originators — Nigeria and Ghana — are fast becoming Africa’s new music epicenter.

Beyoncé’s decision to feature 6 Nigerians: Tekno, Yemi Alade, Mr Eazi, Burna Boy, Wizkid, Tiwa Savage and 1 Ghanaian: Shatta Wale was therefore probably born more out of commercial and cultural considerations, than a respect for tribal accuracies. The singer claims: “I wanted to make sure we found the best talent from Africa and not just use some of the sound or my own interpretation of it.” But despite her best intentions, Beyoncé fell into a predictable geopolitical trap. Any homage to Africa will always be uneven if it doesn’t seek to understand the uniqueness of its people, which often starts with taking Africans serious when they say: Africa is not a country.