Mr Eazi’s debut mixtape Accra to Lagos will be out next month, so there’s no better way to create a conversation around its release than for the singer to do waka to his lesser preferred country and feed off the reaction that follows. Out of a number of cultural elements that Nigerians and Ghanaian disagree on, music is one of the more contentious ones. Unfortunately, the idea backfired and the singer has been roasted by Nigerians ever since he put up this tweet.

Short, jarring and very direct, Eazi has a very engaging style of communication on Twitter that’s almost Trump-esque at times. He says his mind on a number of topics and often doesn’t follow that up with much context. So in under 140 characters, his thoughts can be taken in 140 different ways.

Mr. Eazi has apologized for the tweet yet he’s still getting roasted, some are even (playfully) asking for the singer to be deported forgetting that his real name is actually Tosin Ajibade, Kofi Kentinkrono is just his alias. However, after Nigerians have calmed down from having their panties in a bunch, perhaps we’ll be able to see the larger point Eazi was trying to make.

High Life (in the 30’s to the 50’s)

In order to understand his point, we have to look beyond the “present day” and go as far back to pre-Independence times. There has always been a great deal of affinity between the music scenes in Nigeria and Ghana, owing in part to the shared history of British colonization. There were three waves of highlife music from Ghana into Nigeria – first the Cape Coast Sugar Babies dance orchestra that toured in Nigeria in the late 30’s, then the konkoma highlife brought into Nigeria by Ghanaian migrant workers in the late 30’s and early 40’s. However, Enoch Teye (E.T.) Mensah, the King of Highlife, is widely credited to have propagated the spread of swing-jazz influenced highlife dance-bands throughout West Africa in the 1950’s and 60’s.

ET Mensah

ET Mensah and his dance-band, Tempos, toured around West Africa at the time and spread the music form. When they first came to Nigeria in 1950, highlife was hardly known outside of Ghana. The group influenced the likes of Sammy Akpabot’s Band, the Empire Band and Bobby Benson’s Band to incorporate highlife into their repertoire. But those early groups still played mostly swing and ballroom music, not highlife. Victor Olaiya, who was a trumpeter with Bobby Benson’s Band, was one of the first Nigerian musicians to truly embrace highlife.

Bobby was playing jazz and we were ‘managing’ to play highlife… I had flair for highlife and not jazz. Each time we played highlife, I discovered the floor was always jam-packed. It was a good attraction for me.

After a small falling out with Benson, Victor would break away and form his own band, Cool Cats. They were one of the pioneers of dance-band highlife in Nigeria. Much later, in the 80’s, Victor and ET Mensah would collaborate on a highly successful album Highlife Giants Of Africa – Highlife Souvenir Vol. 1. So the exchange wasn’t one-way, E.T. Mensah too was to be influenced. He brought some of the sounds of Nigeria back to Ghana, infused the style and language on songs like “Nike Nike” and “Okamo”.

Highlife helped influence contemporary music in both countries in the decades that followed. Some of the biggest Nigerian artists today infuse highlife in their sound. Flavour is, for all intents and purposes, a highlife artist, Adekunle Gold calls his music ‘urban highlife’, while Phyno’s last album The Playmaker was almost as much highlife as it was hip-hop.

Afrobeat (in the 60’s 70’s)

Nearly 20 years after his death, Fela’s sound was kept alive in 2016 by his sons Femi and Seun Kuti and by his most ardent disciples Burna Boy, Wizkid, Oritsefemi and D’banj. D’banj’s biggest song in years, “Emergency”, is Afrobeat-inspired and his most recent “Focus” follows the same template. You can hear the influence of the Abami Eda on a number of other popular records, from Davido’s “Gbagbe Oshi” to Skales’ “Temper”; Dremo even calls himself ‘Young Fela’. The title is a bit premature but you can understand the DMW rapper’s haste to be associated with greatness, Fela is the single most important figure in Nigerian music, still.

However, it wasn’t always this way. Fela joined Victor Olaiya’s Cool Cats highlife band as a singer and gained some recognition, but it was actually in Ghana that the singer’s own music really caught on first. Circa 1967, Fela made many trips to Accra and Kumasi with his own group Koola Lobitos, his friend Faisal Helwani organized numerous tours where they’d come out and play. Though it was very early in his career, Fela and company already had a sound. That sound, however, was to evolve and evolve until it eventually became Afrobeat.

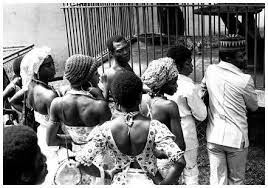

Fela and his wives at the Accra zoo

Fela loved Ghana and would return to the country in the 70’s when he went on self-exile. Afrobeat, the genre title, was coined in Accra but as far as the style of music, some historians attribute some influence to Fela’s association with groups, like the El Sombreros, that he toured with at the time. However, according to Johnny Opoku-Akyeampong (Jon Goldy), of the El Sombreros, this wasn’t the case.

Fela was already sporting his tight-fitting James Brown–like costumes back then. The music was basically the Nigerian style highlife with a jazzy feel to it.

The influence of highlife and the Ghanaian music society on Fela’s career growth is clear but the conversation about whether Ghana had an even stronger influence on his sound is an open-ended conversation. However, what I think is also a conversation worth having is the strain that the hostile immigration policies both countries had toward each other in the 70’s and 80’s had an on the free flow of artists from both countries, hence limiting the musical and cultural exchange.

Hip-life (in the 90’s and 2000’s)

After Fela and Afrobeat in the 70’s, there’s arguably no period more significant for Nigeria’s musical exchange with Ghana than the rise of hiplife in Ghana and, what many consider, to be the golden era of Nigerian music – both in the mid-90’s.

Reggie Rockstone

Reggie Rockstone pioneered a style of music called hiplife, where artists rapped on traditional highlife beats in a combination of Twi and broken English. Hiplife became the contemporary sound of the +233. Over in Nigeria, a fresh contemporary music scene was also on the rise, the rise occurred a few years after hiplife. The sonic influences of the sounds coming out of Nigeria were broader and more inclusive than hiplife though. Nigerian artists infused everything from R&B, soul, funk and hip-hop from the US, to reggae and soca from the Caribbeans, to soukous from the DRC into their music.

Kennis Music is widely credited with helping to bridge the hiplife and emerging Nigerian music scenes. Artists on their roster such as 2 Face Idibia, Tony Tetuila and Eedris Abdulkareem had records like “African Queen”, “My Car” and “Jaga Jaga” that became hugely successful in Ghana – which was significant because there were certain parts of the country where 90-95% of the music on the radio was local music, hiplife, gospel etc.

Kennis has also had Ghanaian group VIP on their roster at different times. The label became instrumental in fostering an environment of cross-promotion, where Nigerian and Ghanaian artists would be able to feature on each others records and those records given proper promotion in both countries. So 2 Face could work with a VIP or a Reggie Rockstone and Tony Tetuila could work with a Tic Tac, and so on. But Nigerian artists where getting far more recognition in Ghana than Ghanaian artists were getting in Nigeria, this lopsidedness would go on till the late 2,000’s.

2 Face and VIP in the video for “MY Love”

Unlike highlife before it and azonto and alkayida after it, hiplife music never really gained a foothold in Nigerian music. Owing to the language and cultural barriers at the time, hiplife music was sparingly reused by Nigerian artists. There were stretches in the 2000’s where a number of hiplife songs crossed over and became popular in Nigeria though, the likes of Bollie’s “You May Kiss Your Bride”, Mzbel’s “16 years” and Ofori Amponsah & Kofi Nti’s “Sweetie Pie” became staples on the radio and at parties. The songs crossed the borders but the artists that sang them and their exciting genre didn’t. Thus, Ghanaian artists were unable to fully capitalize off the popularity of those songs while Nigerian artists continued to thrive in Ghana, loosen up the scene to play more Nigerian and foreign records and encourage a handful of artists to infuse more English and pidgin into their lyrics.

Language and culture were challenges but they weren’t major ones. To my mind, the reason why the musical and cultural exchange of the 2,000’s didn’t favor Ghanaian artists initially was infrastructural; whereas Nigerian labels like Kennis were bold enough to make the investment to take the music round the continent, Ghanaian labels, record companies and promoters didn’t create strong marketing and distribution networks to export their sound outside Ghana. As a result, many big Ghanaian artist were forced to be content with being local champions but regional and international nobodies. There were noticeable exceptions though, people like Kiki Banson teamed up with Westside Music in Nigeria to release Genieve Nnaji’s one and only album in both countries in 2004.

Several years later, a fresh crop of Ghanaian artists like Kwawkesse (the first Ghanaian rapper to be featured on BET) and Tinny tried to make their own path on a bigger stage. Tinny won a Headie award for “African Artiste of the Year” in 2009 and had plans to go international. I had the opportunity to interview Tinny the same year he won the award, and he expressed his thoughts on why spreading hiplife outside Ghana was so difficult.

I think the future of Ghanaian music lies in Hip Life but we need to invest more money in it to be more successful. Music is universal, you can mix the local language with English or Pidgin but you don’t have to do it to be successful.

Ironically, while Nigerian music was far more commercially successful, the individuality and self-sufficiency of highlife was very attractive to a lot of Nigerian artists, while on the other side, some in the artist community in Ghana felt Nigerians were making money off of them but not opening doors for Ghanaian artists when they go back to Lagos.

A few years later, in 2012, Mzbel, another Ghanaian act that later signed to Kennis, spoke about why she felt the traffic between the 2 countries was mostly one-sided.

The main problem is Ghanaian musicians are no longer creating the links in Nigeria like they used to do some years back

Azonto (2013 and beyond)

It lasted for years but hiplife is no longer the dominant force it used to be. Thanks, in part, to a looser, more receptive music scene, other genres like hip-hop and dancehall move the young crowds in Ghana these days. In 2013, those crowds, however, were moving to azonto. Unlike hiplife, azonto came with a portion of Ghanaian culture that was easy to assimilate and reproduce – a dance. Azonto originated from a traditional Ghanaian dance from the coasts. The dance went viral in the UK, where the cultural lines between Nigerians and Ghanaian are blurrier than they seem to be when you go back to the continent. Being a neutral ground and a melting pot of artists from both countries, the UK music scene then became important in the musical and cultural exchange between Ghana and Nigeria.

The race to create songs to capture the azonto movement was won by Fuse ODG, a UK-based Ghanaian artist, but Olamide and Wizkid were runner ups too. “Azonto” (Wizkid’s version) and “First of All” by Olamide became so big in their own right that they introduced question marks about the origins of azonto to the international community, which, I’m sure, enraged Ghanaians the more. Nigerians, once again, were appropriating Ghanaian music and Ghanaian culture. Batman Samini took it upon himself to stand up for his country people, the reggae artist dissed P Square in 2013 over their record “Alingo”, which essentially mimicked the dance and energy of azonto without giving any credit.

Dem dey sound like azonto

The dance kinda look like azonto

So try show me something I dunno

The alkayida movement would follow azonto in 2015, Ghanaian hip-hop artist Guru’s song “Boys Abr?” provided one of the soundtracks for it. Mr. Eazi calls his music Banku Music but if you listen, it’s stylistically very similar to the alkayida sound.

UK-based producer Juls is the architect of Eazi’s music and there is no doubt that Eazi’s trademark drowsy singing and Juls’ drop-stop-kick pattern and mid-tempo sway has been bitten by Nigerian artists and regurgitated in several forms. The style is glaring on records like Runtown’s “Mad Over You” and Korede Bello’s “Do Like That”, two of the biggest songs in the country right now, but subtler on Tekno’s “Pana”, Falz’ “Soft Work”, Koker’s “Kolewerk” and Viktoh’s “Skibi Dat”. Ghanaian pidgin and local slangs are also being used more more and more in Nigerian music.

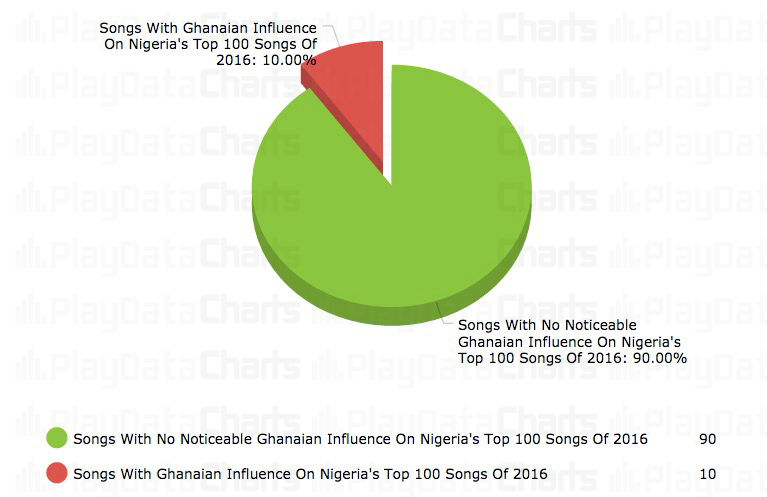

That said, Nigerian music has historically been inclusive and lent itself to outside influence. Of the countries on the continent, Ghanaian music has arguably had the strongest influence over time but music from the DRC, Cameroon and South Africa has also been imbibed. The result is a mishmash of sounds, in fact, part of the challenge with exporting Nigerian music is that there is no one particular popular sound. Playdata recently conducted an interesting study on Mr. Eazi’s claims.

A paltry 10%. While Ghana has had a significant influence on Nigerian music in the past, having a handful of copycat records released in the last few years is not enough leverage to qualify alkayida or banku music as the ‘new sound’ of Nigerian music – Mr. Eazi jumped the gun there. Besides, why the exclusion? Spearheaded by some in the UK music community, there is currently a clamor for all the sounds coming out of Anglophone West Africa to be labelled “Afrobeats” (with an ‘s’). So Eazi’s mindset is regressive because at this point, there has been so much cross-pollination that it is getting harder and harder to draw a clean line to separate what musical influences are Nigerian and which ones are from Ghana.

But at the same time, it is good to give credit where credit is due. You can also understand why Ghanaians would be tired of handing their bigger neighbors salt every time and whenever guests come around the neighbourhood, their neighbours act like the salt was theirs all along. I get that. Historically, the influence of Ghanaian music on Nigerian music has been strong and maybe in 2017, our radio stations and clubs will be awash with more records like “Mad Over You”. But that is simply not the case as of right now, Mr. Eazi exaggerated the influence of Ghana’s current sound on Nigeria’s current music and ought to have expounded on his point of view – that tweet, without proper context, was problematic.

I love the way Mr. Eazi communicates though and I hope that this controversy doesn’t turn him into a recluse on Twitter, like some of his colorless colleagues. I also hope that Eazi’s forthrightness doesn’t cost him dear and the singer is still able to succeed in Nigeria in order to tip the scales of commercial success in the favor of our creatively significant but commercially disadvantaged neighbours. Giving his dual-nationality, the singer is in a unique position to help in doing so.

Sources

Fela – Kakuta Notes by John Collins (Read more)

Ghana Web (Read More)

Hip Hop World Magazine, 2009