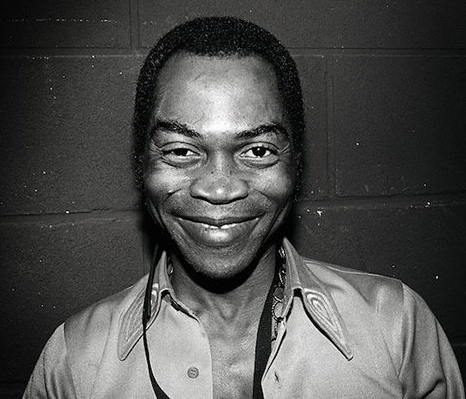

Fela died on the 2nd of August, 19 years ago.

Bringing up a debate about how best to re-purpose the title of the musical legacy he left behind didn’t seem appropriate on the week of the anniversary of his death, so I waited. Legend has it that Fela turns in his grave every time someone uses “Afro beat” incorrectly, I didn’t want my (unsolicited) opinion to be the reason why he did a full 180 on the anniversary of his death.

Continue to rest in peace, Abami Eda.

That said, there’s a conversation to be had, so let’s have it. The evolution of the sound and culture that Fela birthed has been the source of intense debate in recent weeks and this is my 2 kobos.

In a recent interview, Davido tried to articulate the difference between Afro pop and Afro beat from an instrumentation standpoint –

You know the originator of Afro Beat of course is Fela Kuti. Fela has a sound which I can say has the heavy baseline, the Rhodes, brass instrument, and the percussion is different.

The Afro beat sound Davido describes is closest in genealogy to jazz and funk of the 70’s but the delivery is distinctly West African, and infusing traditional instruments like the shekere and local drums gave it that touch. The art form featured chants and call-and-response vocals that routinely stretched for several minutes. New music of this format simply isn’t popular anymore and has not been for quite a while now. That’s part of the reason why Lagbaja and Femi Kuti, respected as they may be, exist in a circuit parallel to what’s considered contemporary Nigerian music.

There are still some younger disciples of this style of music though but for the most part, contemporary artists today just utilize some elements of the sound, pay homage to its creator and keep it moving. 2Baba’s remake of “Jeje”, D’banj’s “Emergency” and Wizkid’s “Jaiye Jaiye” are prime examples but neither artist is called an out and out Afro beat artist.

In fact, rather than calling those particular records Afro beat records, I find that many in the local music community call them Afro beat-inspired or Afro beat-centric instead. Perhaps out of respect for Fela’s legacy, the word “Afro beat” is treated like it’s propriety, and the rights of use are reserved exclusively for the Kuti family, Tony Allen and artists of that era and a select few like Lagbaja. That’s perhaps the reason why the happy medium “Afrobeats” has gained acceptance especially in the diaspora.

DJ Abrantee

Enter DJ Abrantee, a UK-based DJ of Ghanaian descent who is widely believed to have popularized the term. In an interview he granted the Guardian, UK in 2012, the DJ explained-

Africa’s just too big to keep up with all its other genres… This is specifically the western African and: there are a lot of shared ideas between these two neighbouring countries. I see Afrobeats as music which makes the heart beat. And it’s funky, and hyped, and energetic and young

In Nigeria, the DJ has been vilified by some for this but if you give birth to a child and don’t give the child a name, when visitors come around the house and begin to call your child “junior” or “bobo”, who do you blame? Besides, Abrantee did not pluck the name out of the thin air, he didn’t invent anything, he was inspired by his surroundings and used a term that was already floating around.

I remember 9 years ago now, we floated a weekly radio show called “Strictly 9ja” – coincidentally in the DJ’s home country of Ghana – and we threw around terms such as “Naija Beats”, “9ja Beats” and “Afro Beats” to describe the songs we were playing. We were students at the time, so we didn’t know any better but we didn’t have an ulterior motive either, we just wanted to make our sponsors in Accra and Kumasi understand exactly what it was we needed their money to promote – Nigerian music.

Strictly 9ja Radio Show (Kessewaa and Dove FM, Ghana; circa 2007)

Those who live in Nigeria take it for granted that those who don’t need a way to identify our music and differentiate it from other sounds in their immediate environment. That’s the reason why it seems like those outside the country are more proactive about labelling Nigerian music than those who live and breathe it, cue UK Afrobeats. But as we go global, Nigeria can’t run away from its music being labelled.

Why is music labelled? Artists are creatives and creatives, by their nature, hate for their art to be categorized but for branding and commercial purposes, we cannot afford the luxury of not being categorized. Our sound must fit into a format for radio and other global distribution platforms, the style must be differentiated into different charts and award show categories beyond just the “world” category and the culture behind it must be better understood when you ask sponsors, businesses and new fans to invest their time and money into it.

“Afrobeats” is a convenient label to many because it doesn’t defile Fela’s legacy but at the same time it piggybacks off the familiarity of the name to promote today’s mainstream sound. But if we look closely, the strands that do not run through both Afro beat and Afrobeats music are far more than the strands that do. Musically, brass instrumentation is less pronounced today, the music is more synthesized and of course more digitized, so less live instrumentation. The percussion is not rigidly African, we sing or rap, we don’t chant and there’s no way in hell that we are making songs that last for a quarter of an hour. In that way, sonically our music is more influenced by the sounds and culture of hip-hop, R&B and the Caribbean than jazz and funk.

Pres. Jonathan and D’banj, MI and Gov. Ambode

Culturally also, the times have changed, we aren’t fighting for freedom like Fela’s pre-democracy days, our music is apolitical or sometimes, even politically-correct. Artists try to be in the good books of politicians far more than they try to get on their wrong side. Yes, both musical cultures are rebellious but today’s approach is more tempered than Fela’s, even the more trivial expressions of rebellion like marijuana use is implied in our culture and not expressed overtly.

So in that way the relationship between contemporary Nigerian music and Fela’s sound is tenuous, at best we are distant cousins. Afrobeats is therefore more or less a geographical grouping, an umbrella term for music coming out of Africa or more specifically, anglophone music coming out of West Africa that’s heavily influenced by the Nigerian sound.

I have two problems with this – first, aren’t we the first to leap to tell foreigners that Africa is not a country? I know Nigerian music is extremely popular but why are we taking a title that today implies music from the general African or West African region and using it describe a sound from just a part of the continent?

Second, are we seriously going to say merely pluralizing a word gives it a whole other meaning from its singular form? That’s a distinction without a difference, our primary school English teachers will be deeply disappointed to hear this argument. Every time I hear it, I get flashbacks of a late man and it’s not Fela, it’s Sen. Enwerem, who did his best to articulate the difference between Evan Enwerem and Evans Enwerem.

Egbons Don Jazzy and Jimmy Jatt have a suggestion, they suggest that we use global genre labels.

I think it’s limiting when we try to generalize our music under Afrobeats, because under this “Afrobeat”, you have people doing dance music, rappers are there, R&B artists are there and there all categorized under afrobeats artists.

If I’m playing hip-hop, it should be hip-hop by a Nigerian artist but it should fall under that hip-hop category. If I’m playing R&B, it should be R&B by a Nigerian artist. For us not to even limit ourselves within that universal space, so that my music can be nominated in any category in any part of the world, as against saying this is Afrobeats.

Now everything that comes out of Nigeria now says it is Afrobeat.

I agree, but I think we can use two labels actively. We can maintain generic genre labels or prefix them with “Afro” like Afro pop and Afro soul and still have another label that explains that the music is Nigerian and not just African.

Generic labels work best with artists with a distinct and well-understood sound and artists who have excelled in that sound. For instance, Patoranking’s God Over Everything album debuted at number 4 of the Billboard Reggae charts. His sound is distinctly reggae, so it labels itself. But how do you label the mash-up of Caribbean, hip-hop, R&B and dance music peppered with influences from the ghettos of Lagos that Davido, Wizkid and Tiwa Savage practise?

We will do well to learn from the rise of music from other nationalities before ours. In 2004, Puerto Rican music took over the charts and their artists aligned to the local contemporary sound – reggaetón. Daddy Yankee was already a popular rapper but he aligned his sound to reggaetón specifically for that time, Nina Sky were upcoming R&B singers, they aligned too. We too can align to a term or genre regardless of the artist’s primary sound.

Daddy Yankee, Nina Sky, Psy

More recently, the rise of Psy provided the perfect case study for a dual music identity, the Gangnam Style crooner is a hip-hop star and a K-Pop star, K-Pop being Korean pop music, not Asian pop. Imagine if he had described himself only as a hip-hop artist. Using Jimmy Jatt’s logic, can he honestly compete in the same category as the J Coles and Big Seans at award shows? Duality is possible, we can run and chew gum at the same time.

So what’s the solution? I hate to sound like someone who knows 1,000 ways to destroy a house but doesn’t have 1 suggestion on how to build it, but it’s not my place to tell an artist what music they sing, that would be overestimating the importance of a journalist in the Nigerian music space. In Africa, historically it is either musicians that control the narrative like Fela did with Afro beat and Reggie Rockstone did with hip-life or a type of music and culture grow organically from the grassroots in the way galala and kwaito did. But however we want to do it, whether agreeing on Afro beat or Afrobeats or Afro pop or a fourth name like say kpangolo (Majek Fashek), tungba etc, we must be decisive and control the narrative, else someone else will control it on our behalf.

A few years ago, just as the world’s media was beginning to take a keen interest in the Nigerian movie industry, a few taste makers came together to try and fight the propagation of the term “Nollywood”. They didn’t like that it seemed like an unimaginative derivative of Hollywood and Bollywood, the term “Naijawood” was proposed. Sadly, they were too late, Nollywood had already taken off.

It’s not too late here, we still have the opportunity to tell the outside world what to call our local music and avoid a “had I known” moment in the future. If we don’t use it, we might have to accept whatever name the world decides.