I am fortunate to have grown up in an era when, if you heard a rap song on the radio and there was a line you didn’t catch, you could find that song in a ₦100 lyric book, typographical errors and all, and get a more intimate music experience with the rapper.

I am also fortunate to live in a time when advanced technology means I can go a step further than searching for correct lyrics by going to Genius for lyric interpretations, and to also offer interpretations of my own. Sadly, this level of interaction is missing in a lot of the rap music released in Nigeria today.

Lyricism has traditionally been seen as the hallmark of an intelligent MC. The best lyricists use wordplay and storytelling to treat words like pieces of art and encourage the listener to take them as important as, if not more important than, other elements of a song – like the beat, the emotion or the melody.

At least two schools of thought have emerged on lyricism within Nigerian hip-hop. One lays all the blame for the lack of intelligence in lyrics at the foot of the listener. This school supports the notion that rappers ought to dumb down their lyrics, rap slowly and deliver the most asinine of punchlines in order to communicate effectively. They have a point, English isn’t our mother tongue and even if we all smuggled dictionaries into the exam hall, a lot of Nigerians still wouldn’t make a C6 in WAEC English.

Historically, the most successful English-speaking rappers in the country belong to this school and it is hard to argue with success. So when M.I. got defensive recently and said that rappers write ‘wack’ raps because that’s what their audience demands, you understand he isn’t speaking for himself alone.

But perhaps Naeto C explains this mindset best, in 2015, the self-described ‘Only MC with an MSc said: “We (rappers) have ‘regular’ fans who didn’t get the chance to get basic education, and sometimes we have to dilute our music for them to appreciate.”

https://youtu.be/zhCJDINwq3g

Now to the other school of thought, rappers who are aware of the limitations of their audience but still challenge them by providing an informal education to a beat. That way, they do not alienate those with higher English scores and even higher expectations for lyricism, however few.

Wordsmiths like Mode Nine and Boogey are deep-dyed in this school, so perhaps a more progressive artist like Jesse Jagz would articulate this way of thinking best. Jesse once said about lyricism in his raps: “I realize that a lot of people are not literate, however it is my duty as a human being to educate those who are not literate – you don’t treat a sick man by giving them junk to eat.”

Finding a balance between the 2 schools has been the bane of Nigerian rappers’ existence from time immemorial. There has always been a tug of war between remaining smart and dumbing lyrics down, and the early years of development of rap music in the country give us an indication as to why.

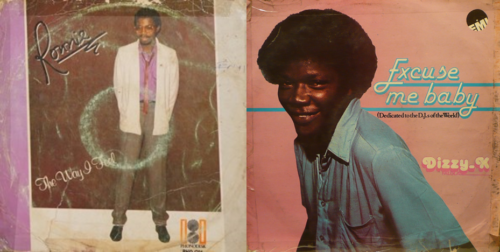

DJ Ronnie, Dizzy K (360Nobs)

Rap music, in a primitive form, first got introduced to Nigeria in the early 80’s, through the work of Ronnie Ekundayo and Dizzy K, but the genre, as we know it today, really took shape in the 90’s. In those formative years, the boom-bap, East Coast style of rap ran hip-hop globally, so most of the rappers we were paying the most attention to were lyrical and wordy. That gave birth to the myth that only English-speaking, hardcore rappers could spit – a myth that’s still perpetuated today – and set a high and probably unrealistic standard for local rappers of that era to meet up.

Interestingly, local rappers too were fans of the same kinds of hip-hop as their audience. In fact, almost every Nigerian rapper that emerged in that era would probably tell you how wordsmiths like KRS-One, Rakim and Wu Tang shaped their style early on. However, taking that style and adapting it to local settings would mean that elements of our culture would have to substitute elements of the hip-hop they imbibed – more often than not, lyricism was one of the first things to go.

This adaptation has been the source of eternal friction between fans of lyricism and Nigerian English-speaking rappers; every rapper who tries to increase their audience by compromising their lyrics is accused of “selling out” or “going commercial” or “going pop”.

A number of studies have been conducted on the relationship between pop songs and the level of education in a country. A recent survey in the US found that the lyrics of No. 1 singles average at a primary 3/grade 3 reading level. So if US pop songs are written with so little lyrical complexity, what chance does Nigerian pop music have?

Having said that, it still sounds like M.I. and Naeto’s school of thought is trying to use our failing education system as an alibi, like they’re trying to pee on our legs and tell us all that it’s raining.

If there is one advantage to doing anything in Nigeria, not just hip-hop, it’s that if the product is good enough, you’ll find an audience. If there is one strategic advantage Nigeria has traditionally used over our continental rivals, it is strength in numbers; we are currently under utilizing it in hip-hop.

Take the currently superior SA hip-hop scene for instance, many would argue that the more cosmopolitan composition of South Africa has helped enlightened hip-hop to find an equally enlightened audience. That may be true but there’s more to this.

If an unashamedly lyrical rapper like Cassper Nyovest can fill up a 20,000-seater stadium in a city of 8 million people, we need to question whether selling out the 4,000-capacity Eko Hotel in a city with more than twice that number of people, is truly a big achievement.

I guess all I’m trying to say is that there are more than enough learned people to appreciate lyricism; remember that this is just a Lagos city vs. Jo’burg comparison. If you cannot find an audience within the 180 million or so people in Nigeria, then I’d question the product you’re offering, and your strategy for reaching the market, before I’d question your potential customers.

Besides, pidgin rap is far more acceptable now than it was in the late 90’s and early 2,000’s, and rapping in your local dialect has never been cooler. Rappers can do either of the two and still be lyrical, hip-hop is deep and wide.

I hate to sound like a pessimist but the education system isn’t going to change soon, not unless successive governments make it a top priority. What can change more easily is a determination to harness our unique advantages rather than to be fixated on our collective shortcomings. What can change is a mindset, and leaders in hip-hop determined to save a dying art form within a stagnant culture; for as long as making dances and pop hits – not creating movements or cultivating a culture or challenging the listeners – remains the only way rappers feel they can “blow”, lyricism will continue to be treated as collateral damage for commercial success.

Originally written for Guardian Nigeria