Through the years, Nigerian artists have endured a love-hate relationship with Alaba distributors – cutting deals with the same group of people pirating your music is akin to dining with the devil, but with a long spoon. However, in the era of digital distribution, there are even more guests at the table, and artists are learning that everyone comes with a spoon that’s much bigger than theirs.

Telcos are the biggest distributors of music domestically; through their bouquet of value added services (VAS), they are able to give tens of millions of users access to a rich database of songs and albums. Telcos take up the lion’s share from the digital sales of the music, up to 80% of the revenue goes to them. So, for instance, if you pay N50 every month to make your favorite song your caller ring back tone (CRBT), your network provider could pocket up to N40 and leave N10 for the artists, their label (if any) and the content service provider (CSP) to split; more on the CSP later.

Since they started operations in 2001, network operators have invested hundreds of millions of dollars in building nationwide infrastructure, hiring tens of thousands of bright professionals and attracting tens of millions of customers. They spend additional millions every month to get new customers and to make sure that their network infrastructure keeps on running. The cost of delivering value added services (VAS), such as access to music, over these expansive networks are significant, but the artist community is adamant that there’s no way that telcos could possibly justify such high percentages simply for transporting and marketing a service.

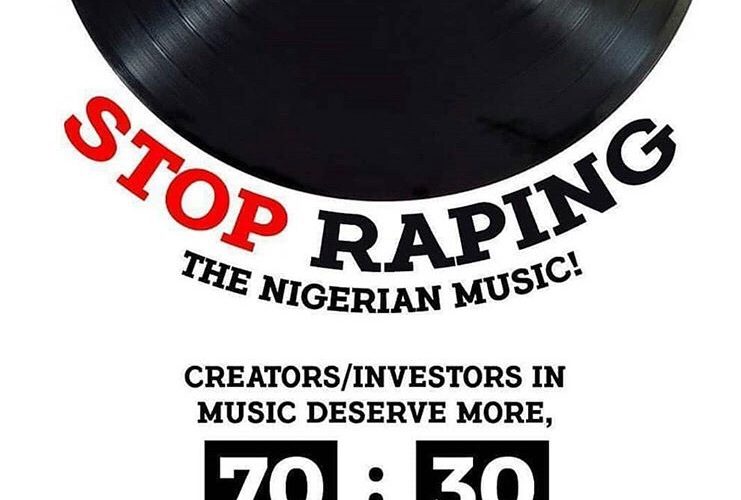

Unable to renegotiate with the powerful telcos, the artist community, through the Pretty Okafor-led Performing Musician Association of Nigeria (PMAN), has taken its case to the government. The House of Reps recently set up an ad hoc committee to give content creators a listening ear, and investigate the operational activities of telecom companies. It was christened #AdhocHearingNov30 on social media, where veteran rapper Ruggedman has become the face of the movement.

Honourable Ahmed Abu and Ruggedman

One of the things PMAN clamored for during the hearing was the enforcement of a 70-30 revenue share in favor of artists, they referenced an existing act to back their case. If the telcos comply, it changes the game forever – independent artists stand to make more money from royalties than their distributors for once, while artists signed to labels now have more money to share than ever before. But when it comes to fighting the middlemen between the artists/their labels and the telcos, the act is powerless, I’ll explain.

One of the most fascinating moments of 2017 was when Ycee – the rapper behind one of the biggest songs of the year in “Juice” – called out Michael Ugwu, founder of FreeMe Digital and the head of Sony Music in Nigeria, for allegedly defrauding him of his royalties.

Michael Ugwu and Ycee at the contract signing

On his Twitter page, while referring to Ugwu, Ycee asked rhetorically: “ever wondered why these execs running digital sharing companies live like they signed all the artistes?” Before answering: “Cos they eating everyone’s [money].”

FreeMe Digital describes itself as “Nigeria’s foremost online digital music distribution network”, it’s essentially a content service provider (CSP) that focuses on music. CSPs handle the technical side of getting a creator’s content on to the telco’s platforms, they then share what’s left of the revenue with the creator after the telcos have taken their cut. If you think that that ‘cut’ is small, think again, about 200 licensed CSPs operate in Nigeria’s VAS provider market, and according to NCC, they currently pull in over $200 million annually and have the potential to do $500 million in the next few years.

In addition to this service, CSPs that focus on music usually provide an interface with foreign online streaming services like iTunes, Spotify and YouTube. What this means is that the CSP can earn even more revenue outside their arrangement with telcos. Yet, despite all this money floating around, many CSPs (not referring to FreeMe) still result to Alaba’s infamous dirty methods of hiding sales figures in order to shortchange artists.

What makes this behavior even more frustrating is that if there’s any time in the history of Nigerian music when it should be easy to trace sales figures, it ought to be right now. In years past, Alaba distributors would boast that so-and-so’s album moved so-and-so number of units after a week or a month or whenever, but there was no true way to independently verify those claims, so they were taken with a pinch of salt.

That said, for all its shortcomings, at least Alaba provides only 2 hops between artist and consumer; there’s only one middleman. With distributing music domestically however, there are 3 hops: the artist/label to the CSP, the CSP to the telcos, and the telcos to the consumer. It’s a long chain that’s about to get even longer.

Toward the end of 2017, the Nigerian Communication Communication (NCC) unveiled plans to introduce yet another hop: content aggregators. These are companies that will sit behind the CSP’s in the value chain and provide a new concentration point for connecting to telcos. According to the NCC, CAs will eliminate the need for CSPs to maintain expensive multiple physical connections to the operators and reduce the number of entities that the operator will have to interface with.

The new value chain will look like this:

Artist —-> Label —-> Content Service Provider —-> Content Aggregator ——> Telco ——> Consumer

The sharing formula for the content aggregators and the telcos is still unclear but even if the 70/30 split that Ruggedy Baba and co are clamoring for gets implemented, there are now enough middlemen to make the entire fight not worth it.

But rather than seeing content aggregators as another (unwelcome) mouth to feed, I see an opportunity for the artist community. Artists now have the best opportunity in years to move further up the food chain than CSPs by coalescing and forming content aggregation companies. The truth is, nobody can protect artist interests better than artists themselves, the coalition of artists that took up stakes in TIDAL streaming service offer a blueprint on how it could be done.

Unhappy with the percentages being paid out by music streaming services, JAY-Z and company took on the mantra “if you can’t beat them, join them”, and launched TIDAL in 2014.

JAY-Z and other artist owners at the TIDAL launch

Taking the “for us by us” model, the streaming service promised to give artists a fairer sharing formula than its competitors. The only reason why TIDAL is able to do so is because streaming services are right next to the consumer on the food chain.

In Nigeria, the FUBU model is a must going forward. For even if the pie gets bigger, the only real way to truly ensure you’re getting a bigger slice is by getting as close to the person holding the knife as possible. We might all hate Alaba, but at least it gives artists that opportunity.

Originally written for Guardian Nigeria