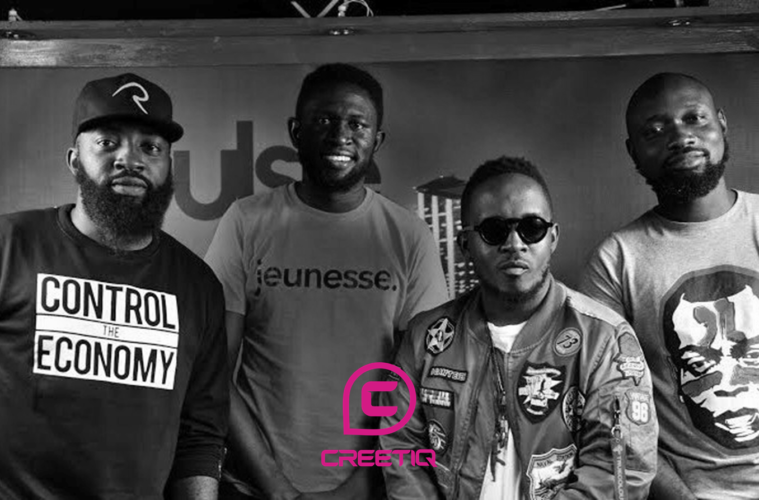

Debate is subjective. It is nothing short of a game of thrones – explicit, vicious and scheming with unending plot twists where there is hardly hero or villain, victor or vanquished. And the (anything but) “Greatest Podcast You Ever Did In Your Life” debate featuring Pulse.ng’s Osagie Alonge, Ayomide Tayo and Chocolate City CEO Jude Abaga aka M.I. sadly lived up to this billing.

After almost 3 hours of heated debate, the real problems were left unaddressed while the future of the creative and cultural industry in Nigeria remained bleak as no truth was reached. Like debate, right and wrong, truth is subjective. Is The Chairman the best-performing Nigerian rap album of the last 3 years? Was Tayo’s open letter to M.I. on Pulse.ng shabbily-written and short on facts? Do Nigerian culture journalists need to see things first from the artist’s perspective in order to write more informedly? True, although that depends on your school of thought. But is it not also true that there is a dearth of creative genius by most Nigerian artists in recent times as chronicled in the Loose Talk narrative, or that journalists and critics must write and curate history without fear or favour? These and many other premises are as true as they are also untrue depending on the context, point of view or, as displayed in the expletive podcast, the loudest voice. Truth is subjective and anything that is subjective is also debatable. But unlike truth and debate, criticism is not subjective.

According to T.S. Eliot, one of the greatest literary critics of the twentieth century, creative faculty expresses itself in the synthesis of existing ideas but critical faculty creates new ideas through analysis and discovery by seeing objects as they are. While artists may be more interested in perception as it relates to subjective observation of their works, critics ought to base their perception on objective observation. Culture is vivacious and rich with new and fresh ideas and artistes are needed to harness their intellectual energy and convert it into great art. But when ideas become stagnant and the free exchange of ideas are stifled, as we are currently experiencing with the overbearing wave of the “pon-pon” sound, criticism is needed to help create fresh and foster a free flow of ideas. Criticism should be removed from self, objective and free-from all personal ideologies or political agendas. It is neither a game of truth nor is it a show of prowess and should never be debated in any form or medium.

It is unfortunate that while the creative and cultural industry in Nigeria is only just warming up to criticism, internet trolling between critics and artists and debates, like the Pulse.ng podcast, are only giving criticism a bad name and widening the gap in the industry even more. In the short term it may increase likes, followership and awareness; take M.I’s upcoming Young Denzl album (or is it 5 albums?) and the Loose Talk podcast. But in the long term, criticism is much more than a PR campaign for damage control. Fresh ideas stem from criticism. It is not enough to be a gifted artist. Without new ideas, artists would lack the necessary raw materials for great art. Likewise, an artist’s work is also an important catalyst for critics to expand and create new ideas. Both artist and critic are interdependent.

Criticism is probably the most important means to grow the creative industry in Nigeria. Yet it is the least celebrated. The outcome of The Critic Challenge organized earlier this year by CREETIQ – foremost review aggregator of African movies, music and books, showed that there are only a handful of critics in Nigeria. And of these, only a small subset writes objectively or understands what criticism demands. There are probably other good critics out there who shy away from criticism because of what it connotes in the Nigerian context, or simply because they do not see it as a rewarding venture. The other majority have devised diplomatic ways to water it down so they do not come across as offensive. Finding good critics in Nigeria should not be as difficult as the proverbial needle in a haystack.

Criticism is as much a science as it is art and the numbers actually count for creative content to attain critical acclaim. Aggregating critical commentary in large numbers is the solution to the unending strife between criticism and the creative and cultural industry in Nigeria and Africa in general. This would help content providers, creatives and consumers of creative work make data-driven decisions based on an aggregate of critical reviews summed up by a calculated score rather than on an individual’s opinion. The CREETIQ system is trying to achieve this by appraising reviews from various critics in the socio-cultural scenes in Africa and assigning an average numeric value to each review relating to its degree of rating of the work. Since its launch in January, almost 5,000 critics and reviews have been aggregated on the CREETIQ platform. But there is still much work to be done for criticism to have the desired impact.

There is an increase in the demand for Nigerian creative content globally. Equally, there is an upward rise in the volume of music released each year including books and indigenous Nigerian movies in cinemas (the sheer number reaches over 10,000 unique titles per year). And this presents a new challenge in making data-driven decisions. But the metrics to measure commercial success and quality of creative content in Africa are inchoate. It is practical that if demand and supply both increase significantly, quality would also have to increase to demand a higher premium.

According to Wilfred Okiche: “Criticism is a bitter pill to swallow but it is so crucial to development”. The truth is that a deliberate and concerted effort must be made by artistes, critics and stakeholders alike to use platforms available to them to bridge the gap between criticism and the creative and cultural industry in Nigeria to foster growth. Criticism on its own is not truth. In the 2007 classic animation, Ratatouille, the imperious and acerbic food critic Anton Ego concludes that “In many ways, the work of a critic is easy. We risk very little yet enjoy a position over those who offer up their work and their selves to our judgement. We thrive on negative criticism, which is fun to write and to read. But the bitter truth we critics must face is that, in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is probably more meaningful than our criticism designating it so. But there are times when a critic truly risks something, and that is in the discovery and defence of the new. The world is often unkind to new talent, new creations. The new needs friends… Not everyone can become a great artist, but a great artist can come from anywhere.”